On Literary Fantasy

Last June (2021), an English professor complained that students today only read fantasy books and not proper “modern literature”, such as his book, available in paperback. That click bait spawned Twitter debates on the nebulous concept of “Literary fiction”. Discussion went off in multiple directions, not entirely connected to the original theme. I collected those threads below.

|

|---|

| Jonah and the Whale (1621) by Pieter Lastman |

As an infant, my mother read Ladybird editions to me, often tales from the Brothers Grimm: Jack and the beanstalk, Red Riding Hood, Rumpelstiltskin.

As a child, I read the Bible often. It begins with a talking snake and ends with dragons and the horsemen of the apocalypse. You don’t have to be religious to appreciate religious books, you can enjoy them as fantasy.

There are great monsters and action scenes. Daniel surviving the lion’s den, Job haunted by visions of chaos-beasts, so many more. The first great American Novel was Moby Dick, about a sailor spooked by a psychopathic whale. It was, in part, a retelling of Jonah’s troubles with the murderous waves and the giant sea monster.

The Bible contains the “best bits” of six hundreds years of written culture based on an oral culture of storytelling that goes back to the stone age. A lot of similar written material from the same era is being discovered. Some stories made it into the canon of the Old or the New Testaments. Far more fell by the wayside. Hundreds of gospels (stories of Jesus’ life) were written, only four made the cut. The stories and letters that became the New Testament were written before 70 AD, but they didn’t have the binding technology to put them into one edition.

The ancient Jews and others wrote with scrolls. Papyrus wound around a wooden roll, not unlike a huge version of toilet paper. They become unmanageable after about twenty thousand words and have an upper limit of thirty-thousand words. You can’t fit many in box or a cupboard.

English is wordier than ancient languages, but the most concise of English translations, the Authorised Version (US: King James Version), had 783,137 words. Finding a format for the Bible was largely the reason that the codex format (what we call a book) developed from Roman military notepads. The canonical version of the anthology we call the Bible certainly existed by 367 AD. It was the first bestseller, and the offer of eternal life was one heck of a “reader magnet”.

|

|---|

| The Silent Highwayman by John Leech (1858) |

At middle school, we performed “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. I was the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, the beginning of a slight goth tendency that I still have to keep in check.

We pretended to be elves and men shapeshifted into donkeys for Shakespeare’s Midsummer Nights Dream. Macbeth begins with three witches. We read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: jousts, ladies and (spoiler alert) more shapeshifting.

At University, I learned ancient Greek and a little Latin, read Homer and Ovid’s fantasy epics and the Bible again, this time in the original languages, and the scriptures of the other great religions that include flying ponies, multi-headed goddesses and so on.

I read other books too, of course, but the above are unquestionably literature, yet fantasy too.

|

|---|

| Fan art by Özlem Karalar |

“The market for high-end literature isn’t a healthy one. Intellectuals are reliably penniless, and fancy reading habits don’t make you cool any longer. The people who actually buy books, in thumpingly large numbers, are genre readers. And they buy them because they love them.” - Damien Walter

All fiction is a fantasy. Every novel requires conceits and unrealistic elements to keep the story moving even if set on planet earth within known history. The idea that “popular fiction” is not “literary” comes from the puritanical Edwardian era. An academic funding model that allowed a privileged minority of people to tell their stories.

The future will forget all modern “high-end literature”, but it will remember “Fifty Shades of Grey”. It’s the most popular book in a “realistic” setting. I never got past the free 10% sample, so apologies if Ana uses her newly gained knowledge of whips and ropes to catch and ride wargs, defeat an Orc invasion, and discover the lost island of Atlantis in orbit around Venus.

The book opens with a budding student journalist Kate, who, after years of trying, lands an interview with a reclusive but world-leading businessman. She feels ill so sends her flatmate, Ana, who has never heard of him. Kate is lucid enough to brief Ana and write her a list of questions.

Total ham. Firstly, rearrange the meeting. Secondly, any real journalist would drug themselves or strap themselves together somehow to get the scoop. However, it serves a purpose. It allows the reader to discover Grey through Ana. Readers accept it.

You must be willing to suspend disbelief. It’s the same if the novel is about a wizarding school where pupils are invited by owls delivering letters. In the final showdown between Harry Potter and Voldermort, they chat and point sticks at each other. If Harry called in Apache gunships and revealed himself to be a cyborg, it wouldn’t be any more or less “literary”.

I was told off for going off on a tangent about Fifty Shades. So I asked for an example of literary fiction. They suggested Ulysses. I would describe Ulysses as an urban fantasy novel, based on the epic fantasy, Homer’s Odyssey.

|

|---|

| Elevator Alarm by Andrew R Dieselducy |

E. L. James and J. K. Rowling are extremely rich and successful so can be used as examples. Modern “Literary Fiction” authors are not. Let’s tread carefully and make up an imaginary book by Dr Joe Bloggs, Junior Lecturer in English at the University of Southend:

An executive argues with his wife. On the way to a career changing meeting, the lift breaks down. The help button is broken. His phone has no reception. Four hundred pages of mid-life crisis, discussion of all the lines and cracks inside the lift, the author talking about his pet political ideas, then the protagonist dies of thirst.

His book about a guy dying in a lift (US: elevator) won several literary awards and got great reviews from half of his fellow English dons (the other half were not his friends so trashed it). Sadly, no one else read it. It took him five to ten years to publish, so the political ideas passed irrelevant and seemed quaint.

His University decided to abolish English Literature to teach coding to the children of developing world government officials. Joe took up residence in a tent under the Gravelly Hill Interchange. He expects his next work to be a critical success and get him a new academic position.

|

|---|

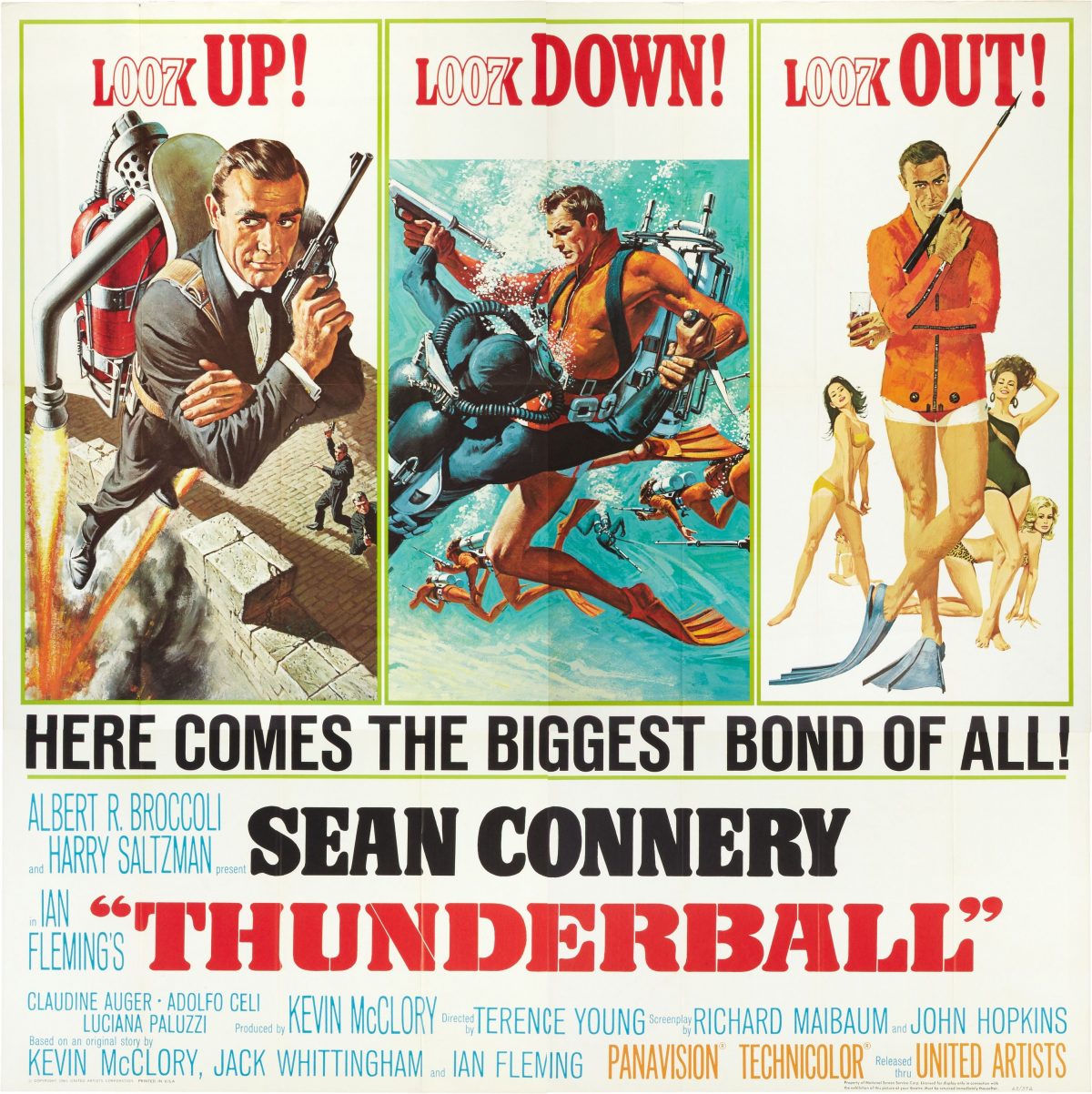

| Thunderball poster (1965) |

“George Eliot’s novels are literature and Ian Fleming’s are not,” says “The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory.”

Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels made a vital exploration of individualism vs collectivism in the Cold War era and questioned British identity after the fall of the empire.

Of course, the movies went in an increasingly slapstick and commercialised direction until they became product placement vehicles for cars, menswear and watches. Who even wears a watch? In a crowded place, shout “Hey Google, what’s the time?” and a thousand devices will answer.

Fleming himself dumbed down the books to please his publisher, keen to make more money off the back of the films, even retconning in a Scottish noble backstory to explain Sean Connery’s accent. An author has to eat somehow.

|

|---|

| 007 - Licence to Sell Overpriced Watches |

[Not sure where the quote below came from:]

“Literary authors nowadays are frequently supported by patronage, with employment at a university or a similar institution, and with the continuation of such positions determined not by book sales but by critical acclaim by other established literary authors and critics… On the other hand… genre fiction writers tend to support themselves by book sales.”

So literary authors write unreadable books, i.e. bad books, and pat each other on the back? An important part of art is to enlighten the audience with your thoughts, i.e. they must be readable.

“Literary fiction, by its nature, allows itself to dawdle, to linger on stray beauties even at the risk of losing its way” - Terrence Rafferty, 2011.

In other words, they need an editor to delete a load of it? If the reader gets to the end cover, the book found its way.

If the concept of literary fiction is dead, it doesn’t matter. Terminology dies, great fiction lives on. I went through a list of thirty novels considered literary fiction. They all fit within the following genres:

-

Coming of age

-

Existential crisis/mid-life crisis

-

Tragic love stories

-

Road trips

-

Period novels, especially slavery/plantations

The term “Literary fiction” is best replaced by differentiating different ideas (not exhaustive list):

-

Classics: Old books filtered by the sands of time.

-

Boring books that fitted the critic’s political views.

-

Niche books by English professors.

|

|---|

| Lia Turtle by David Revoy |

You may have noticed I discovered how to embed images, did I over do it? I haven’t plugged in a comment system yet though, however, you can respond to me on Twitter. Tell me what you liked/hated and it will help me to write more. We started this post talking about click bait, on that topic, I joined the evil empire and started a Facebook account. Please like and befriend me or whatever the heck we are meant to do there.